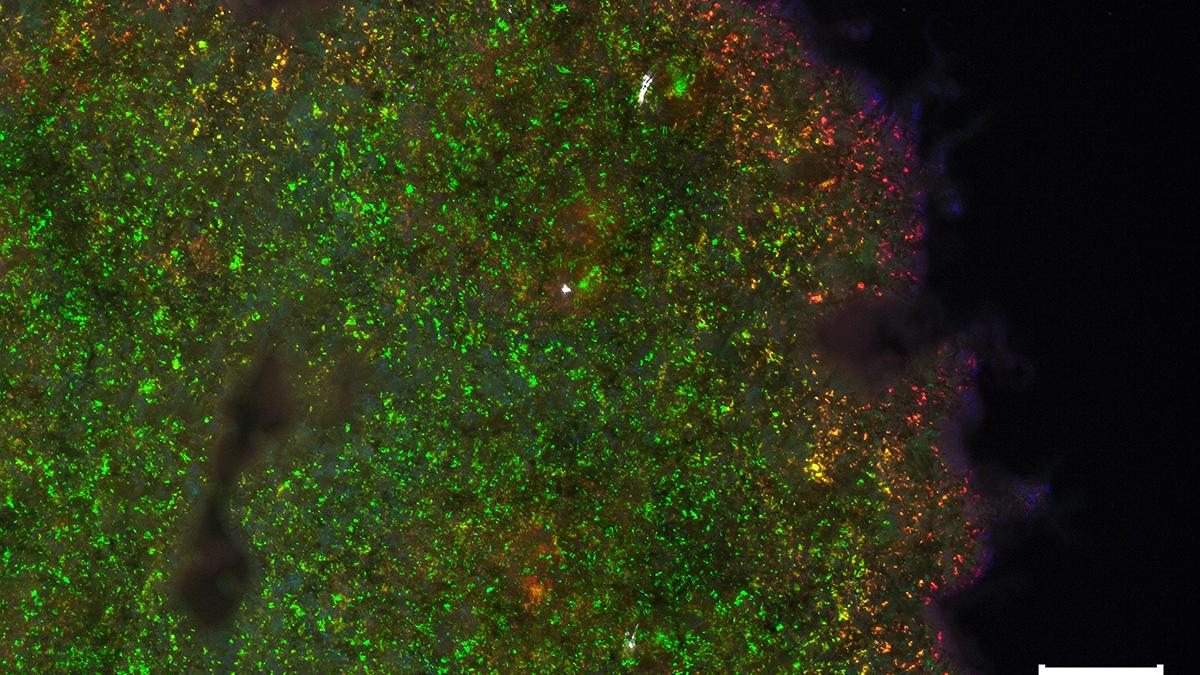

Iridescent biofilm after 24 hours of growth at different magnifications. 30x. (Courtesy Jamel Ali)

Researchers at the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering have uncovered how marine bacteria self-organize to produce vibrant, iridescent colors—opening new possibilities for eco-friendly sensors, coatings and biomaterials.

“In the future, we might see camouflage or adaptive display technologies, where these pigment-free, structurally colored materials change appearance in response to their surroundings, much like a chameleon.” – A. Scutte, Ph.D., postdoctoral researcher

Bacteria Engineered to Create Nature’s Living Color Palette

Some of nature’s most brilliant colors—peacock feathers, butterfly wings, beetle shells—achieve their shimmer not through pigments, but through microscopic structures that bend and scatter light. Now, researchers from the Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering at the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering have discovered how to harness this same phenomenon in living bacteria.

The team recently revealed how certain microbes self-organize on soft surfaces to form microscopic structures that create vibrant structural colors without any pigments, as demonstrated in a new U.S. Air Force-funded project published in Advanced Functional Materials.

Postdoctoral researcher Annie Scutte and Associate Professor Jamel Ali at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory investigated the environmental factors controlling these striking pigment-free colors in bacterial biofilms. These motile bacteria demonstrate how living organisms can create customizable colors, offering scientists a blueprint to engineer advanced biomaterials with unique optical properties.

“By understanding how these structures produce color, we can design bio-inspired materials for sensors, coatings and paints,” Scutte said. “Unlike traditional colorants that use expensive or toxic chemicals, biofilm-based structural colors could offer cheaper and safer ways to make colored materials.”

How Marine Bacteria Create Living Photonic Systems

Structural coloration occurs when vivid, shifting colors are created not by pigments but by light interacting with microscopic structures within an organism. While common in butterfly wings and peacock feathers, this effect is less understood in microorganisms.

The researchers investigated Cellulophaga lytica, a gliding marine bacterium that forms dynamically iridescent biofilms. They found that environmental factors—especially surface stiffness and salt content—control the hues seen in C. lytica biofilms.

By altering these environmental factors, the team demonstrated they could influence bacterial motility and organization at the microscopic level, changing the colors produced by the biofilms.

“Over time, how bacteria organize controls the iridescent colors,” Scutte said. “By influencing cell movement, we can tune different hues, such as making a structure reflect more red. This lets us design living, color-changing materials without traditional pigments.”

Environmental Mechanics Drive Bacterial Color Production

Using advanced imaging and rheological techniques, the team demonstrated that growth surface properties—such as agar stiffness and salt content—are crucial to iridescent color development.

Stiffer substrates enhanced early bacterial motility, resulting in thick, organized biofilms with intense green iridescence. Changing the salt altered the substrate’s viscoelasticity, disrupting movement and shifting the biofilm toward redder colors.

The research shows that environmental mechanics directly influence how bacteria self-organize to create vivid structural colors. This understanding enables the design of living, customizable materials that react to their environment, with applications in biomaterials, optics and synthetic biology.

From Lab Discovery to Real-World Applications

The research team identified several promising applications for these living, color-changing materials.

Environmental biosensors could visually indicate changes in pollution levels by shifting color in response to toxins or salinity variations. As Scutte explains, these sensors might detect changes in water or air quality through observable color transformations.

Another area involves developing pigment-free coatings that use structural color instead of dyes. Because the color results from physical organization rather than chemical pigments, these materials resist fading or chipping better than traditional paint.

“In the future, we might see camouflage or adaptive display technologies, where these pigment-free, structurally colored materials change appearance in response to their surroundings, much like a chameleon,” Scutte said.

Advancing Biomaterials Through Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Study co-authors include Jaideep Katuri, Samuel Omeke, Nellymar Rivera-Santiago, Cianna Williams and Claretta Sullivan. The project received support from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, National Science Foundation and NASA.

Interdisciplinary collaboration at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory played a key role in the research. The findings highlight the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering’s leadership in biomaterials research and sustainable materials development.

Editor’s Note: This article was edited with a custom prompt for Claude Sonnet 4.5, an AI assistant created by Anthropic. The AI optimized the article for SEO discoverability, improved clarity, structure and readability while preserving the original reporting and factual content. All information and viewpoints remain those of the author and publication. This article was edited and fact-checked by college staff before being published. This disclosure is part of our commitment to transparency in our editorial process. Last edited: 01-15-2026.

RELATED ARTICLES

Chemical engineers receive over $1 million in NSF grants for multi-institutional bacteria research

$1.4M NIH grant helps FSU researchers clean carcinogens from groundwater